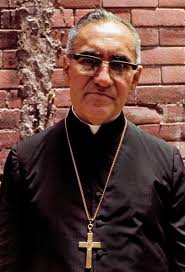

Oscar Romero: Presente!

March 25, 2013

March 24, 1980. San Salvador. On that horrific day, in the middle of saying Mass, Archbishop Oscar Romero – a humble priest who dared to fight oppression from the pulpit – was murdered by the Salvadoran army. Now, thirty-three years later, Servant of God Oscar Romero (considered the unofficial patron saint of the Americas) continues to inspire those who seek peace and justice throughout the world.

It is often said that Romero’s brief ministry shares much in common with that of his Lord. Like Jesus, Romero led a relatively uneventful life for many years before beginning his mission. (When elected archbishop of San Salvador, he was considered a bookish intellectual who would make no waves in a time of political turmoil and struggles between the wealthy landowners and the exploited campesinos). Like Jesus, he lived most deeply and fully in the last three years of his life and became a champion of the poor and marginalized.

Initially moderate in his opinions, Romero was inspired by his Jesuit friend Rutilio Grande (who was also murdered by government forces) to take up the cause of the poor. In his weekly sermons – heard throughout El Salvador and beyond by radio – he regularly denounced the government with his death squads, disappearances, and general reign of terror it was enacting on the country. Like Jesus, he ultimately paid with his life for his beliefs and commitment to justice. And, like Jesus, Romero is still very much alive in the minds and hearts of millions – Catholic and non-Catholic alike – who would seek to follow his example in standing up for the poor and oppressed.

The recent election of Pope Francis does not initially invite comparisons with Romero. As much of the media has eagerly pointed out, Cardinal Bergoglio also lived through a dictatorship, and he did not respond as Romero did. While some sources report his attempts to protect the lives of those in danger, others note his links with the dictator Videla. While this issue is certainly complex, I find myself in agreement with Brazilian theologian Leonard Boff’s statement that “What matters is not Bergoglio and his past, but Francis and his future”:

http://iglesiadescalza.blogspot.ca/2013/03/leonardo-boff-what-matters-isnt.html

Francis is not perfect, and he is no hero…But then, neither was Romero when he became Archbishop. I am not sure what Bergoglio thinks of Romero, but in advocating a “Church of the Poor” he is certainly expressing the spirit of his continent’s unofficial patron. And while I know better than to place too many expectations on a pope – especially in the troubled Catholic Church of today – I hope that the Latin American church will be inspired to look at its richly progressive past, perhaps revisiting the theology of liberation and breathing new life into it for our twenty-first century world.

Meanwhile, I know I join my voice with millions when joyfully I cry out, “Oscar Romero…Presente!”

Habemus Papam

March 13, 2013

Francis I…Even the name fills me with hope. Let’s pray that our new pope – the first Jesuit, the first Latin American, the first in a long time to choose a new name – will renew the Catholic Church in the spirit of love and simplicity that Francis of Assisi revealed to be at the heart of Christian life.

As the Catholic Church awaits the election of our next pope, the Church has once again become the subject of considerable media attention. As churches continue to close, as the priest shortage increases, and as we acknowledge the fiftieth anniversary of the Second Vatican Council, more and more people are saying that the Church needs to change. One of these is Joanna Manning, a former nun who, after years of struggling to change the Church from within, eventually gave up and converted to the Anglican Church. You can read her story here:

I can certain empathize with Manning and others who have left Catholicism for Anglicanism. I can also empathize with the Roman Catholic Womenpriests who have been ordained within the Church (the first women priests were ordained illegally by male bishops sympathetic to the women’s ordination movement) and have suffered excommunication for their conviction. However, many questions follow from this discussion. The first question I would offer the author of this article would be to what extent the Church’s treatment of women really is the cause of Catholicism’s declining numbers (especially among the young). One comment on the article suggests that the decline Church membership is not particularly due to the hierarchy’s stance on social issues such as gay marriage, women’s ordination and contraception; rather, it is due to a general secularization taking place in the culture. In terms of qualitative, anecdotal evidence, I would argue that young people are leaving the pew behind for both of these reasons. I am wondering…to what extent are issues related?

My next question is…for those Catholics who want to reform the Church, what would the best strategy be? Joanna Manning and many others like her have their strategy – they vote with their feet. The Roman Catholic Womenpriests have their strategy, but unfortunately, their radical defiance of the Church’s rules threatens to alienate them not only from traditionalists, but also moderate Catholics who might be sympathetic to the cause but hesitate to defy the church authority so boldly. Some moderate Catholics have suggested, for example, that fighting for women’s access to participation in the deaconate might be a good first step (before fighting for full-blown ordination). This point also deserves further discussion and will be addressed in an upcoming post. Meanwhile, your comments are welcome!

CBC Interview with Father Roy Bourgeois on the Current

December 22, 2012

http://www.cbc.ca/player/News/Canada/Audio/ID/2318390447/

A 30-minute interview with Father Roy Bourgeois, founder of School of the Americas Watch and advocate for women’s ordination. It’s worth listening to this inspiring man’s powerful words.

Surprised by Joy

December 18, 2012

Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice. Let your forbearance be known to all, for the Lord is near at hand; have no anxiety about anything, but in all things, by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be known to God. Lord, you have blessed your land; you have turned away the captivity of Jacob

- Philippians 4:4–6; Psalm 85 (84):1

Christians throughout the world are now celebrating the third week of Advent. Two days ago we celebrated “Gaudete Sunday” – the day of rejoicing. I’ll admit that, as I dragged my feet to Mass and skulked into the church halfway through the psalm, I didn’t feel in anything like a joyous mood.

I’ve spent the past several weeks (or perhaps months) in a slight malaise. Lately I feel I’ve been going through the motions of my own life – dragging myself to class or choir rehearsal, but letting my mind wander during every meeting ; gripping the handrail in the subway, my face buried in a book I’m only half-reading, and refusing to notice the people around me.

Meanwhile, the current and projected future state of our world does not provide much cause for rejoicing. I’ll admit that the horrific reality of the Newtown, CT shooting has not quite set in with me. Somehow, any news transmitted by mass media lately has a way of feeling less than real. But unfortunately, rape, murder, torture, cruelty in every form is all too real. I firmly believe that we are all capable of committing these horrific acts, and they are taking place everyday, all around the world.

Where are we to find light amid all this darkness? How can we rejoice even when the reality around us looks so bleak? A partial answer in this past Sunday’s liturgical readings and also from the priest’s homily. Gaudete Sunday – the day of rejoicing. But what does it mean to rejoice? Does it mean the same thing as to be happy?

According to the priest celebrating last Sunday’s Mass, happiness and joy are two very different things. The former has to do with our circumstances. As he explained it, happiness is something often very fleeting that comes to us from outside – often from having our needs and desires met. Joy, on the other hand, is internal. It lies deep within us, perhaps buried at times, perhaps intangible when we find ourselves face to face with adversity. And yet, for Christians, this joy is nothing passive. It is a light that shines through every darkness, giving us the courage to keep walking in the night.

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not a very happy person, and my current profession (if I dare call it that) as a graduate student in the humanities is not the most conducive to happiness (parasitical and privileged as we lovers of learning may be, we inhabit a social space that tends to cultivate and validate the “Woe is me” attitude). But even before I became a PhD student, my moods tended toward the lugubrious, and I’ve often envied my more ebullient friends and acquaintances who, no matter what injustices or difficulties they encounter, never stop smiling.

And yet…I can also say that while I’ve never been particularly happy, I am very familiar with the kind of joy that is celebrated on Gaudete Sunday. It’s not the magical, radiant, festive joy of Christmas. It is much more subdued, a moment of rose amid a season of penitential purple. It’s not the joy of fulfilled desire, but that of eager, patient waiting for a fulfillment that we hope will come.

Just as I’m not a particularly happy person, I’m also not a patient person – especially in this age of instant communication and instant gratification. And yet, the joy we celebrate on Gaudete Sunday is very familiar to me. It was there when, as a teenager, I struggled at finding myself in the middle of my parents’ marital conflicts, and it helped me to give my mother the support she needed during what was a very difficult time. It was there in my last year of college, as I panicked at the prospect of having truly to take charge of my own life and decisions for the first time. It was there during my first job as a high school teacher, in which I found myself unable to overcome my inexperience and anxiety while dealing with some very unruly kids.

“Sometimes you’re happy,” a deeply spiritual Evangelical Christian friend said to me during that time. “Sometimes you’re unhappy. But God is always present.” I initially balked at what seemed like his trivialization of my misery, but as time went by I started to understand. Even when I most dreaded the morning commute to my job, even when I came home in the evening only to collapse on my bed in exhaustion, there were still moments in the day when something – an encouraging word from a colleague or an engaged class discussion – would fill me with the joy that comes in the midst of struggle.

As of this writing, I have not yet read C.S. Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised by Joy. And yet, I find the title intriguing. Joy is indeed something that tends to take me by surprise. I was shocked when last night, while reading about a small nonprofit organization’s efforts to save endangered languages in New York City, I experienced a feeling I hadn’t known in quite a long time: excitement. It was a sudden stirring, a sudden bubbling up of a feeling that, though not always felt, is nonetheless present, an underground river rushing below the surface of everyday life.

We are not living in happy times. Violence continues to plague the world; many people are suffering due to the global economic crisis; inequality is increasing; environmental and technological upheavals loom ahead. As for the personal level…I have no doubt that the kinds of personal problems I’ve described in this post are trivial when compared with the ones that you have experienced. However, I am convinced that the joy that Catholic Christians celebrate on Gaudete Sunday is not specific to Christians or indeed to any religious people alone. Surely you can to relate to a moment when, in a time of great personal struggle, you also found yourself surprised by joy.

We are not the first humans to live in uncertain times. To rejoice – to follow that light still flickering within us, no matter how dark the road – has rarely been easy, at least not for the vast majority of human beings. And yet, we are still called to remember this river that sustains us, this nourishment from within that no one can take from us.

When will the Church stop silencing its true prophets? In support of Father Roy Bourgeois, Maryknoll Missionary, now and forever

November 20, 2012

November 19, 2012. It’s a sad day for Catholics. Maybe not for all Catholics, but definitely for those who believe the Church’s foundation lies at the bottom rather than the top. Today, a voice crying out in the wilderness, a voice of justice, peace and hope in our turbulent times, a voice calling for openness and inclusion has been silenced. What are Catholics to make of this? All that Father Roy Bourgeois did – other than taking a stand for peace in his twenty-two year-old struggle to shut down the SOA/WHINSEC at Ft. Benning, Georgia – was to listen to his own conscience and publicly express his support for women’s ordination. Given that the Vatican has declared that this issue should not even be discussed publicly, the decision to remove Father Roy from the priesthood is hardly surprising. Nevertheless, I am indignant. From the time I was very small I was told that WE are the Church – not the priests and nuns, not the privileged few wandering around Vatican City in their big hats, but US – all of us. And I think I speak for many of us when we say that we will not defrock our priest. Father Roy, we will not let your voice be silenced.

To read the official announcement on Father Roy’s dismissal, I invite you to read this article from the National Catholic Reporter: http://ncronline.org/news/people/maryknoll-vatican-has-dismissed-roy-bourgeois-order

And, to read an interview I conducted with Father Roy in September 2012 (coincidentally published by Rabble.ca today, November 19, just a few hours before his dismissal, please read on:

Father Roy Bourgeois never thought that he would one day become a Catholic priest. “I was raised Catholic, but as a boy I really didn’t take the religion very seriously, and I always thought that priests were weird,” says Bourgeois, who grew up in Louisiana during the 1950’s.

He also never imagined that he would become a social justice activist. “As a white male living under segregation, I never questioned the system, nor did any of the Catholics around me … Black Catholics sat in the last four pews, and we referred to segregated schools as ‘our tradition.'”

Indeed, this description hardly seems the profile of the man who would later go on to found the School of the Americas Watch — one of the largest and most vocal components of the anti-war movement in the western hemisphere. But, when he signed up for the U.S. navy in an eager attempt to leave Louisiana, Bourgeois had no idea just how dramatically his life was about to change.

After volunteering to fight in the Vietnam War, he was compelled to encounter realities he’d never considered before. “I went to Vietnam thinking that we Americans would be liberators – the same kind of thought that the US always uses to justify its invasions,” he says. “Instead, I witnessed violence beyond my imagination.”

Faced with constant danger and vulnerability, Bourgeois noticed his faith growing more important to him. By chance he met a Quebecois missionary priest running an orphanage for Vietnamese children, and he began doing odd jobs there when off duty. “This missionary was a true healer; he wasn’t seeking to convert the children to Catholicism, but merely to understand and help them. He was a true inspiration for me … The Vietnam War was pure madness, but in the orphanage my life had meaning.”

On the advice of his new mentor, Bourgeois applied to the community of Maryknoll Missionary priests and was accepted into the seminary. His family was surprised by his decision, but they supported him emotionally and raised funds for his missionary work. Upon his ordination, Bourgeois was assigned to work in a poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of La Paz, Bolivia, where he soon encountered the ideas of liberation theology — a strain of Catholic thought that applies Christian principles to the social realities of the poor and oppressed.

“My spiritual and political awakening began in Vietnam, but it continued in Bolivia,” says Bourgeois. “I’d been raised in a hierarchical, patriarchal, colonial model of the church that said the poor should embrace their poverty and look forward to happiness in the next life. In Bolivia, I encountered a model of God as an all-loving being who’d made us all equal. Liberation theology resists the idea that each individual must seek his own salvation; it’s much more community-based. The struggles of others became my struggle.”

Not all Catholic leaders in Bolivia shared this commitment to liberation theology; indeed, some openly favoured the dictatorial regimes that had taken hold of much of Latin America by the 80’s. But Bourgeois, who visited prisoners and learned of documented torture cases, continued to investigate this transnational issue. “Hundreds of churches were talking about the School of the Americas in Latin America, and the more I learned about this horrific abuse of U.S. military might, the more concerned I became.”

Founded in 1946, the School of the Americas is an elite institution of the U.S. army that has trained Latin American military personnel in a variety of areas, including torture techniques. When the 1989 massacre of six Jesuit priests in El Salvador was exposed as having been completed by SOA graduates, Bourgeois transformed his concern into action.

Since 1990, the organization he founded has fought tirelessly for the closure of the SOA, lobbying government leaders and raising public awareness of the impacts that U.S. military policy continues to have in Latin America. Every November, thousands of concerned citizens from around the Americas gather with Bourgeois and other SOA Watch activists outside the gates of the Institute’s facility at Ft. Benning, Georgia for a vigil commemorating the dead. Although the name of the institution was changed in 2001 — it is now known as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), its faculty and central purposes remain unchanged.

About five years ago, Bourgeois was joined by former Maryknoll Lay Missionary and human rights activist Lisa Sullivan. Together, they decided on a new strategy toward closing the school: removing its students. Travelling throughout Latin America and meeting with multiple political leaders, Bourgeois and Sullivan have found this strategy to be somewhat successful. Beginning with Venezuela, they eventually got Bolivia, Argentina and Uruguay to withdraw their troops. Last summer, a meeting with President Rafael Correa ensured Ecuador’s withdrawal. In a September meeting with Bourgeois, Sullivan and a delegation of SOAW activists, Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega announced that his military would also be withdrawing its own remaining troops, making Nicaragua the first Central American country to withdraw formally from the SOA.

“When we see an injustice, silence is the voice of complicity,” says Bourgeois, who has served time in the U.S. prison system for entering Ft. Benning during previous vigils. “I’ve always believed in the primacy of conscience, which enables us to discern right from wrong.” This commitment has led Bourgeois to confront not only the state, but also his own church. For the past three years he has spoken openly about what has become a taboo topic in Roman Catholicism: women’s ordination.

“In the old model of the church, preached since the Fourth Century, God speaks to his people only through men,” says Bourgeois, who cannot help but notice a correlation between the structural sexism of the Catholic priesthood and the institutional racism he experienced in 1950’s Louisiana. “But in liberation theology, God speaks through everyone. Don’t we profess that men and women were created equal? Who are we male priests to say that our call to the priesthood is authentic while women’s is not? No matter how hard we try to justify our discrimination against others, it is not the way of God.”

Although Bourgeois’ support of the Catholic women’s ordination movement has drawn censure from the Vatican (to the point of being pressured to “recant” his position or face excommunication), he has remained as passionately devoted to this issue as he has to closing the SOA. “Our conscience is a lifeline to God,” he says. “When I fail to follow it, I feel torn and conflicted. On both of these issues, my conscience has old me to speak clearly, boldly and with love. This is what I have done, and this is what I will continue to do.”

(Original article can be found at http://rabble.ca/news/2012/11/seeking-peace-through-justice-interview-father-roy-bourgeois-founder-school-americas-wa)

From BBC News: Catholic Church attracts future priests using Facebook

September 10, 2012

Apparently God’s call now comes virtually:

Was Cardinal Carlo Martini the last liberal Catholic bishop?

September 9, 2012

I certainly hope that he was not. But, even in the case that he was, I am certain that the voices of liberal Catholics, though faint, are not going away:

Words of Wisdom from Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann, M.M.

September 9, 2012

Every so often we meet someone whose every word seems to be filled with the divine inspiration. During my recent trip to Nicaragua, I was blessed to meet such a someone. Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann: Catholic Maryknoll priest, former Nicaraguan Foreign Minister, former President of UN General Assembly, art collector, revolutionary, sage. Although he believes strongly in nonviolence, he also believes that the Nicaraguan Revolution of 1979, which toppled the forty-year Somoza dictatorship, was a just war against imperialism. As the group I was with (a delegation of US and British citizens working for the closure of the School of the Americas) and I listened to Father Miguel talk, we were all struck by his insight and wisdom. I would like to share with you several quotations from his address to us, interspersed with images from his home (which he is gradually converting into a museum of Nicaraguan art).

“To follow Jesus means to live a life of risk. We cannot be Christians and reject risk. Otherwise, we run the risk of losing contact with Jesus.”

“I believe that the gospel of Jesus, my Lord, is radically nonviolent. There is no greater violence than imperialism.”

“The Church has never been in favour of a revolution to benefit the poor. This is because the Church is an old institution that for much of its history, has worked in cahoots with the empires and has accrued many privileges. The privileged classes hate, fear and despise revolution. This has been a lamentable fact.”

“When I was six years old, I asked my father why the Mass was so important. He said it was important because it pleases God. This answer was enough to carry me for a few years. But then, one time while attending morning Mass with my mother, I saw some people looking for food in the garbage. I asked her, ‘Mother, why are they hungry?’ She responded, ‘Because it is not true that we are Christians.’”

“Lord, help me to understand the mystery of your Cross, to love your Cross, to embrace my own cross in whatever form it comes.”

“The Cross was a death penalty reserved for anti-imperialists. The thieves that were crucified on either side of Christ were called bandits. That was the term used to describe people who opposed imperial power. When Christ was crucified, all Palestine was a beehive of anti-imperialism. Christ’s message could not be more subversive; he preached the kingdom of God as a counter-force to the kingdom of empire. The difference between him and those crucified with him was that while they were armed, he was not. His gospel was of nonviolence.”

“The worst crimes in the world have been committed in the name of obedience. Obedience must be to God and to the primacy of conscience, not to man.”

“What the world needs most is spirituality. The church has silenced its own prophets. By ‘prophets’ I don’t mean people who foretell the future, but people who see that humanity has derailed, who call us back to brotherly relationships.”

“Christianity has to do with moving from the logic of I and mine to the logic of we and ours.”

“Spirituality means being constantly ready to give our lives like our heroes and martyrs did.”

“There is no revolution without spirituality, and no spirituality without revolution.”

“Don’t fall into the temptation of not loving your country, or not loving our harlot mother Church. Thank God that we are all sinners, so that we might have compassion for other sinners.”

“If we receive applause, beware – we are betraying Christ. We must be foolish in the eyes of the world. The wisdom of God is foolishness for the worldly.”

“Our encouragement must be in Jesus. Forget everything else; cling to Jesus.”

“The world is in bad shape; we are in need of people inflamed with love. I pray that you all may receive a shot of divine insanity, the insanity of the Cross. It is this insanity that makes us yearn to risk our lives for those people on the other side of the tracks.”

Last weekend I visited my family in Buffalo, NY, and I also attended my home church of St. Stanislaus (founded in 1873 by my great-great uncle, a Polish priest who was a leader in Buffalo’s diasporic community during the nineteenth century). Every time I return to St. Stanislaus I marvel at its splendor and beauty – a beauty that truly inspires the viewer to contemplate the presence of the divine.

Unfortunately, as I have already mentioned in this blog, several of Buffalo’s urban churches are under threat of closure by the diocese, and many have already been shut down. The reasons for this are manifold. While a general decline in church attendance by the younger generation is a contributing factor, Buffalo continues to be one of the most heavily Catholic areas of the United States. The more salient issue, in my opinion, is the general decline in population in the area (many people leave Buffalo due to lack of economic opportunity) and the continued division between the city and suburbs (Buffalo is one of the most racially and socioeconomically segregated cities in the United States). Many of Buffalo’s historically and architecturally significant churches are located in its poorest, most crime-ridden neighborhoods. Even though some local activists are working to revitalize these areas, progress remains slow. The area remains full of abandoned buildings, broken shutters and vacant lots covered with litter. While some of the closed churches have been purchased and used for other purposes (occasionally still as houses of worship) many have simply been left to rot.

As the oldest ethnically Polish Roman Catholic Church in Buffalo, St. Stanislaus is currently shielded from this fate. But, it cannot be taken for granted. If the diocese was able to close St. Adalbert Basilica (allowing it to be used only as an oratory for weddings, funerals and other special occasions), there is nothing to stop them from closing any other churches that they choose to. But then, maybe there is something – us!

You may wonder why this matters. I am aware that most of you who read this blog are not from Buffalo, NY. In fact, most of you aren’t Catholic. But this is an issue that goes beyond any specific religion, culture or location. As I have stated earlier, historic preservation is a question of values. Many of us simply shrug our shoulders whenever an old, historic building in our community is torn down to make room for a new apartment complex. However, many of us also understand that these historic sites – be they houses of worship or any other old buildings – are part of our human heritage; they serve to connect us to our past while assuming ever new meanings in the present. For me, St. Stanislaus is such a place. And so, while I am only just beginning to learn to take proper photographs, I hope to share a bit of its beauty with you.